Home > Ferdinand Magellan

Ferdinand Magellan (Sabrosa, October 17, 1480 – Mactan, April 27, 1521) was a Portuguese explorer and navigator, among the first to reach every continent on Earth. He was born into an aristocratic family in a small town in northern Portugal, but became an orphan at the age of 10. Two years later, he moved to Lisbon, where he became a page at the court of King John II of Aviz.

In 1505, at the age of 25, Magellan was sent to India in the service of the viceroy Francisco de Almeida. He later took part in an expedition to the Moluccas (an archipelago in present-day Indonesia), and in 1510 he was promoted to the rank of captain. However, this title was soon revoked because he had strayed from the fleet with his ship in search of new lands further east.

After participating in the conquest of the port of Malacca (in modern-day Malaysia), he returned to Portugal. But soon after, in 1513, he joined another expedition to Morocco, following which he was unjustly accused of trading with Muslims, an allegation that cost him his position at the Portuguese royal court.

In the early 16th century, following the discovery of the Americas by Christopher Columbus, several expeditions were organized to search for a route to the eastern seas. As awareness grew that this was in fact a new continent separating Europe from Asia, the urgency to find such a passage increased.

Various explorers had discovered new lands in both present-day North and South America, but none had found the long-sought passage. Some had ventured as far south as the Río de la Plata, between present-day Argentina and Uruguay.

Thanks to his previous experiences and the study of contemporary maps, Magellan developed a plan to reach the Moluccas by sailing southwest. He became convinced there was a passage through the southern part of the American continent.

Given Spain's interest in these territories, he turned to the Spanish king, who agreed to finance the expedition, hoping to find a shorter route to the East Indies than the one that skirted around Africa, now firmly controlled by the Portuguese. There was also the prospect of claiming new lands for the Spanish Empire.

It is also important to note that the Treaty of Tordesillas, signed in 1494, had divided all non-European territories between the Portuguese and Spanish empires. Lands east of the 46° 37' West meridian belonged to Portugal, those to the west to Spain. Thus, it was unclear to whom the Moluccas, the fabled Spice Islands, then controlled by the Portuguese, actually belonged.

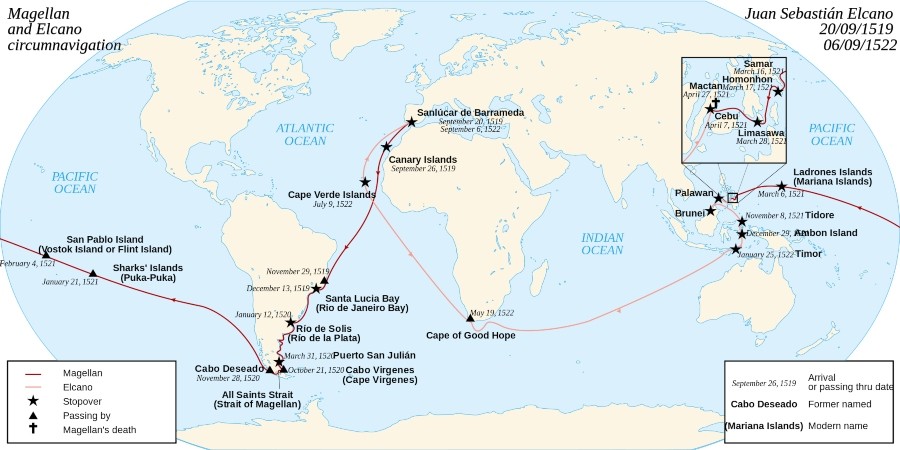

Magellan’s expedition, composed of five ships and 234 men, departed on September 20, 1519, from the port of Sanlúcar de Barrameda, in Andalusia. From the start, the fleet had to evade pursuit by Portuguese ships sent by King Manuel I, who sought to stop this endeavor, especially because it was being led by a Portuguese navigator.

After taking shelter in the Canary Islands, which at the time already belonged to Spain, the expedition resumed course a few days later and sailed toward Brazil. They reached the Brazilian coast on December 6 and anchored in the bay of Rio de Janeiro, but not before quelling a mutiny by Spanish officers who had not yet fully trusted Magellan.

The search for the elusive passage to the Pacific through the Río de la Plata, along with a new mutiny, slowed the expedition. They were forced to spend the harsh southern winter in the Bay of San Julián in Patagonia, the southernmost point reached by Amerigo Vespucci in 1501. In May 1520, the ship Santiago was sent ahead to scout the coast, but it wrecked a few days later. Fortunately, most of the crew made it back overland.

Magellan resumed the journey in October with the four remaining ships as the weather improved, and finally discovered and navigated through what is now known as the Strait of Magellan, entering the Pacific Ocean on November 28, over 14 months after setting sail from Spain! At this point, the captains of the other three ships were given the option to return home. Esteban Gómez took this opportunity and turned back with the San Antonio.

Both the Pacific Ocean and the strait itself owe their names to this voyage. After struggling through the Atlantic, the three remaining ships found calm seas and favorable winds in the Pacific. During their passage through the strait, named Todos Santos by Magellan, campfires were seen burning in the distance at night. This led to the naming of Tierra del Fuego, the southernmost landmass of South America.

Hoping the hardest part of the journey was over, the fleet sailed northward along the Chilean coast to Valparaíso before heading into open sea, aiming to reach the Moluccas within a few weeks.

In reality, it took 3 months and 20 days before they sighted land again. The crew was near exhaustion. Much of Oceania was still completely unknown to Europeans, and Magellan’s route brought them to Guam in the Mariana Islands without encountering any other islands along the way.

Soon after, they reached the Philippines, with about 150 men still surviving. Among them was an interpreter who knew the local language. The islands, including Cebu, were annexed to the Spanish Empire, and King Raja Humabon and many of his subjects converted to Christianity.

Upon learning of the Spanish presence, the nearby island of Mactan resisted. Nevertheless, Magellan decided to land there on April 27, 1521, confident he could subdue it as he had done with Cebu. Instead, he was killed in battle.

Magellan’s death led King Humabon to renounce Christianity, and about thirty more Spaniards were killed. One of the remaining three ships, the Concepción, was burned, and the surviving members of the expedition fled to Borneo, where they reorganized under the leadership of Juan Sebastián Elcano.

The Moluccas, specifically Tidore, were finally reached on November 8, 1521, over two years after the expedition had begun. The local inhabitants, discontent with Portuguese rule, welcomed the Spaniards and helped them load the two remaining ships with valuable spices. They set sail westward for home. However, the Trinidad suffered mechanical failure and was eventually intercepted and captured by the Portuguese.

Elcano, now left only with the Victoria, first reached Timor and then navigated across the Indian Ocean, carefully avoiding the coasts controlled by the Portuguese. After rounding the Cape of Good Hope, he was forced to stop at the Cape Verde Islands to resupply. There, thirteen crew members were imprisoned by the Portuguese authorities.

Finally, on September 6, 1522, after 2 years, 11 months and 17 days, the expedition ended where it had started, with only 18 survivors who had completed the first circumnavigation of the globe.

Among them was Antonio Pigafetta, an Italian geographer and writer who kept a detailed account of the journey. Thanks to his writings, we can relive what was perhaps the most fascinating and extraordinary adventure of the Age of Exploration in the 1500s.

This expedition proved or reinforced several important facts: it confirmed that the Earth was round, not flat; that its circumference was much greater than previously estimated; that the American continent could be circumnavigated and finally, that traveling westward results in the loss of a day. Pigafetta himself noticed this, having meticulously recorded the dates throughout the voyage. When he returned to Sanlúcar de Barrameda, he believed it was September 5, but the actual date was September 6.